Increasing the circularity of packaging - can resetting how recycling rates are calculated help?

EPR schemes have the power to advance the circular economy, but they need to be designed properly. TOMRA has established five design principles of high-performing EPR schemes. This series will take a deep dive into each of those principles. First up: Circularity.

For decades, it was common practice to estimate packaging recycling rates based on the volumes or weights sent to material recovery facilities (MRFs), rather than the amount of that material that could actually be recycled. This method made it seem as though efforts to increase recycling were on the rise, but the truth is that only a small fraction of packaging materials are actually reprocessed into new products of similar quality. Could this approach do more harm than good by perpetuating myths about recycling?

Recyclability depends largely on local circumstances, including the infrastructure that exists for collecting, sorting, and recycling waste. To improve recycling rates, packaging should follow general design-for-recycling (DfR) guidelines. Even when the packaging elements are fully recyclable, the composition of waste can make it difficult to be effectively sorted at MRFs. Therefore, decisions made in the design stage of packaging play a critical role in determining its potential to be recovered and returned to the supply chain, ultimately replacing virgin materials. While there is not yet one global standard, several free resources for designers have emerged in different regions. For example, The Association of Plastic Recyclers Design Guide Overview and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and IDEO partnered Circular Design Guide.

Even in countries that are leaders in their recycling efforts, a significant percentage of packaging materials are disposed of through incineration (with or without energy recovery) or landfill because the packaging wasn’t designed for recovery. As packaging has become more technical, it often results in multiple materials or layers, adding complexity to the recycling process. Plastic yogurt cups with removable paper sleeves and aluminum foil seals, for example, are not always separated by consumers before they are placed in the recycling bin.

Globally, circularity for packaging still has a long way to go. A new report by The Last Beach Cleanup revealed that plastic recycling rates in the United States have fallen from 8.7% to close to 5% over the last four years. While the recycling rates in the United States are largely stagnant, some countries are progressing more quickly. The European Union’s ambitious Single-Use Plastic Directive (SUPD) targets are driving change throughout the system – reducing waste and increasing circularity with well-designed policies that lead to high-performing Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes for packaging.

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR): Vital for packaging circularity

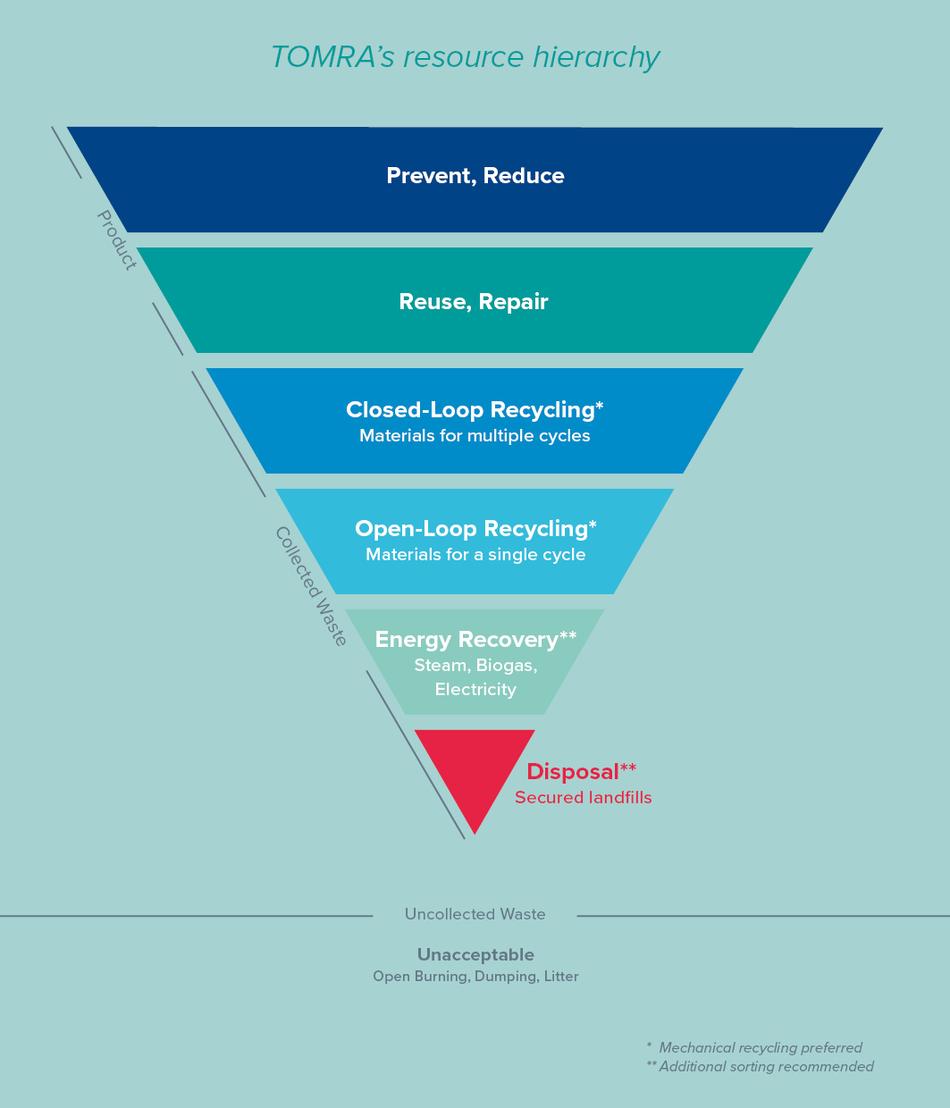

Effective EPR policy supports the establishment of systems that prioritize a resource hierarchy, incentivize eco-design, and utilize reliable measurement protocols. It creates a framework that reduces reliance on virgin materials by emphasizing resource efficiency and quality.

The waste hierarchy is an internationally accepted standard that aims to keep materials at their highest and best use by establishing an order of waste management options from most to least preferred based on the ecological and social impact. TOMRA’s resource hierarchy expanded on this concept to prioritize methods that employ the least carbon-intensive processes and differentiate between open-loop and closed-loop recycling. To ensure materials are continually turned back into new products of the same or similar application, closed-loop recycling systems (e.g., bottle-to-bottle) offer the most sustainable opportunity for increasing circularity beyond reuse.

As a guide for designing an EPR scheme, the TOMRA resource hierarchy helps policymakers establish definitions, set targets, and measure performance. In practice, closed-loop recycling is still in its infancy, with recycled polyethylene terephthalate (rPET) at the forefront of sustainable plastic packaging. While open-loop recycling, such as making clothing fibers out of water bottles, reduces our dependency on virgin resources, there is a missed opportunity to keep materials at their highest and best use, and it offers fewer environmental benefits than closed-loop recycling.

If post-consumer packaging materials continue to be processed but not returned to the supply chain, it creates a bottleneck for a circular economy. Therefore, it is essential for EPR schemes to clearly define what does and does not count toward recycling targets. TOMRA’s white paper, EPR Unpacked – A Policy Framework for a Circular Economy, examines the different approaches for calculating recycling rates. While targets can be set and measured at different points in the value chain – mainly collection, sorting, or recycling – the calculation point to support real progress should be as close to the final recycling step as possible.

Instead of estimating recycling rates based on the amount of material sorted for recycling, TOMRA’s recommended calculation point reflects the volume of material sent for reprocessing. Depending on the material, this could be the point before sending it for remelting, extrusion, pulping, etc. This ensures that contamination, pre-treatment losses, and residues are not included in the recycling performance numbers. Moreover, this calculation point helps policymakers offer transparency to the public and convey a system’s ability to recycle collected packaging materials.

For more detailed information on the benefits and drawbacks of various calculations methods, download the complimentary white paper.

Boosting circularity with recycled content and eco-design

In recent years, numerous jurisdictions and companies have implemented circular economy policies, and the demand for recycled content has significantly increased. Eco-modulated EPR fees can incentivize packaging’s recyclability and the percentage of recycled content. Such measures make higher ranking options in the resource hierarchy more financially attractive than the lower ranking options.

By financially rewarding companies that use recycled content in their packaging, EPR schemes help reduce reliance on virgin materials and enable circularity. France is a prime example of encouraging eco-design through its bonus-malus method as part of the EPR scheme for packaging. When producers integrate post-consumer recycled content (PCR) into their packaging, they can receive a bonus of up to 50 percent, reducing their financial contribution to the system.1 In addition to basic EPR fees, companies are penalized for packaging that interferes with recycling processes and rewarded for packaging that meets sorting guidelines.

As part of an eco-design strategy, the incorporation of recycled content plays an important role, as it directly stimulates the effective remanufacturing of resources into new products. PCR mandates are the best way to achieve circularity and effectively avoid the excessive greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions caused by primary production. Additionally, EPR schemes with mandatory targets for recycled content are key enablers in creating market certainty and stimulating investment.

Circularity is only one of the five design principles of high-performing EPR schemes. Stay tuned to learn more about the other essential aspects and don’t forget to download our series of white papers on EPR now.